The Indigenous Quichua People

Ethnonyms: Kichwa, Qquichua, Quechua, Kechua Countries inhabited: Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador Language family: Andean Equatorial Language branch: Aymara-Quechua

With a population of around 2.5 million, the indigenous Quichua people of northwestern South America are the largest of any indigenous population group in the Americas today.

Aymara-Quechua languages are, collectively, the most widely spoken of all indigenous languages in South America. The Quichua are also the only indigenous people to have migrated both southward, along the ridges and valleys of the Andes Mountains, and eastward into the Amazon Rainforest. This early divergence in their migration paths has created distinct mountain- and jungle-Quichua identity and culture.

The Quichua were among the earliest peoples to be conquered by the Inca Empire. Ironically, the Inca Empire comprised mainly people who spoke the same Quechua language. It wasn't until Spanish colonization, though, that their population level fell drastically. One of the most important dates in history is associated with this decline.

November 16, 1532 marked the capture of the Inca Emperor, Atahuallpa, by the Spanish conquistador, Francisco Pizarro. This blow to the Incas was the single biggest factor in allowing further Spanish expansion in the region, bringing with them the diseases that would eventually wipe out millions of indigenous peoples.

Today, we must distinguish the ethnolinguistic Quichua from speakers of Quechua. The latter total somewhere around 10 million, since many speakers of what are now extinct languages later adopted Quechua as their language. Numbers are impossible to confirm, but some have suggested that there are more Aymara-Quechuan speakers in South America today than when the Spanish first arrived.

Spanish colonization has, over the past five hundred years, created significant changes in Quichua culture. Before the Spaniards arrived, the Quichua were pre-literate — having no true writing system. However, they developed a way of recording events by tying knots in cord. Inter-marriage with Spaniards was practiced from the early days of colonization, creating "Mestizos" (who are now oficially counted as a separate ethnolinguistic group). One has to venture into very remote communities these days to find majority "pure-blood" Quichua.

While Roman Catholicism is today widespread, following the efforts of (mainly Spanish) missionaries, Pagan and Animist tradition co-exists alongside it.

Some of these photographs were taken at the annual two-day La Virgen de las Mercedes festival (known locally as Fiesta de la Mamá Negra) in Latacunga, Ecuador. Officially a Roman Catholic religious celebration, alcohol is unavailable on the first night of the festival.

The second day begins with a traditional Catholic mass; it is easy to believe you are in Rome. Immediately after the mass, a statue of the Holy Virgin is carried through the streets. Locals throw garlands at the statue in hopes of receiving blessing and good favor. Then, just as the day before, cross-gender dressing and masked-and-costumed street dancing form the bulk of the festive activities.

The public parade of sacrificed pigs, decorated with assorted dead animals, packets of cigarettes and bottles of alcohol, is also seen. Men wear these ritual, Pagan offerings to the spirits like a backpack as they accompany the dancers and musicians through the streets. This festival is probably the best known of all Quichua celebrations — it is certainly the best known indigenous peoples' festival in Ecuador. I know of no official comment on this "Roman Catholic" festival from the Vatican, but it surely must not approve.

Venturing outside Ecuador's major cities, one comes across more sober, yet equally traditional Quichua festivals. Many of these festivals are often off-limits to outsiders. In a tiny, remote Andean mountain village I was able to attend the local oratorio festival; a celebration of village unity that, although not strictly off-limits, outsiders are seldom encouraged. An all-day festival, as early as six o'clock in the morning the villagers are to be seen in their finest clothes heading for the village square.

Songs (sung in Spanish these days) proclaim and celebrate traditional Quichua values and beliefs. The whole song cycle is well planned and, by the look of it, well rehearsed, as the men and women, who stand in separate groups, know when to sing their verse and when to gesture their acknowledgement of what the opposite sex is singing to them.

In the afternoon, once school has ended, the villagers reconvene for light-hearted fun and games that carry yet symbolic meaning. Women pair up — some are even roped together — in a sort of "mad hatters'" competition. The aim is to see which duo can wear the most number of hats. Of course, the significance is not in the winner so much as it is in the symbolic message carried by participating in the contest, which is that any one villager will help shoulder the burden of the others.

In another display of unity, the women of the village remove their ponchos and lay them alongside each other on the ground. A group competition, the aim is to tie all the ponchos together into a single "string" of ponchos faster than they achieved at the previous festival.

In these remote communities, the visitor gets a sense of what life must have been like for the earliest Quichua settlers. Subsistence agriculture, a constant battle for survival against the elements, the domestication of indigenous animals, spiritual beliefs transcending their migration route all the way from Africa and a pioneer attitude to continue their exploration despite the challenging mountainous terrain, have all contributed to a Quichua culture that survives today.

Although they live in countries that are now "officially" Spanish-speaking, the visitor is well-advised to avoid a mistake I first made; before attempting to communicate with young children or elderly adults in Spanish, consider "international sign language" as a better option. It will take a few more generations before remote, isolated Quichua communities adopt Spanish en masse as their first language.

Set in more modern times, yet changed little over the centuries, a centralized, weekly marketplace gathering of outlying Quichua communities is a place to witness a part of their history that has changed very little. The man pictured above carries a table weighing more than himself to market in hopes of selling it. In times gone by he might have carried a heavy animal. But if he doesn't sell it this week, he'll be back next week.

The lady pictured below sells food at market. I was fortunate to capture a photograph of her during a moment when she had no prospective customers. She was offering a prayer — perhaps to ask for more customers — which she then blew out to the wind. Her action may appear to represent a "primitive" belief to Westerners. Yet the Quichua have believed in this kind of spiritual contact for many generations.

Many Quichua have migrated eastward into the Amazon Basin. Because of the different landscape, climate, indigenous plants and animals, their culture has developed separately from that of their southward-migrating cousins. Rainforest Quichua have remained more isolated from the historical forces that have shaped the northwestern parts of South America. Rivers, not roads, are the primary means of transport. Electricity is provided, if at all, by solar panels. Spanish is spoken much less than in the mountains. Only the larger communities have schools. As the one pictured below shows, facilities are very basic. For many of these rainforest Quichua communities, their primary contact with the outside world is by battery-powered radio.

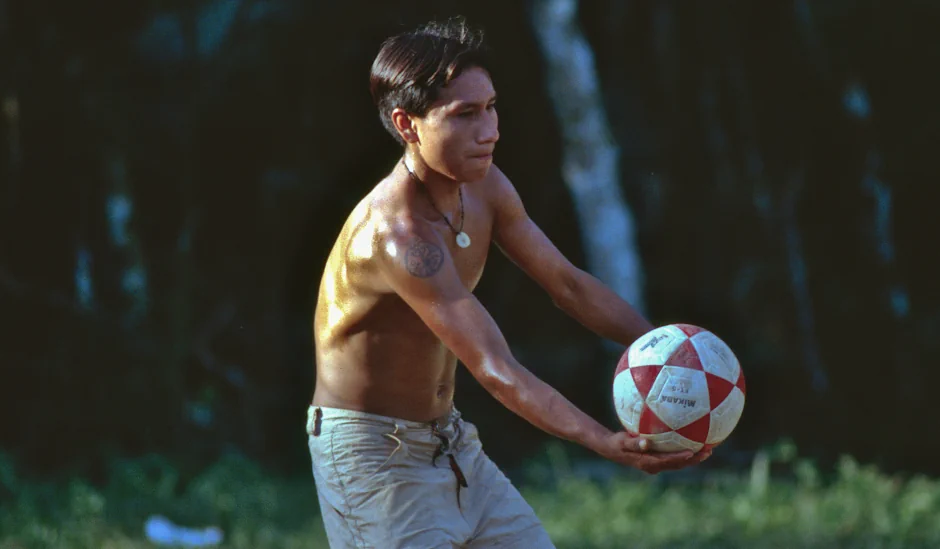

Even in the rainforest, though, life is slowly changing for the Quichua. Volleyball and soccer are the sports of choice today. Western style clothing has all but replaced traditional dress. Missionaries have achieved a high degree of religious conversion.

In one rainforest Quichua village, I witnessed a wedding anniversary. Looking very Western, the couple were celebrating their 15th year together. They held a very traditional, Catholic gathering, much like we might have attended ourselves. Their village has electricity, is majority Catholic and is close to and accessible by road from a larger Ecuadorian community.

Still, despite all the changes brought about by these factors, this same village has a traditional shaman trained in ancient rainforest Quichua practices of magic and healing. To this day, for example, he prepares tea from the ayahuasca (roughly translated from the Quichua as "vine of the spirit") plant, an hallucinogen used by many rainforest peoples for ritual clairvoyance, healing and spirit worship.

The single biggest change affecting the rainforest Quichua today is the encroachment on their land by oil and logging companies. Although this has been happening for the past forty years — and it affects other indigenous groups in the region too — the Quichua are among those impacted most recently. Due to lack of education, many do not realize the potential long-term impacts on their traditional livelihood. Only very recently have they been able to form organizations with enough size and unity to begin bringing their cause to world attention.

Photography copyright © 1999 - 2026, Ray Waddington. All rights reserved. Text copyright © 1999 - 2026, The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R. (2003, revised edition 2023), The Indigenous Quichua People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved March 2, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Quichua>

Web Links Quichua Cousins of the Andes and Amazon Upper Napo Quichua Dialect "We are the World" sung in Quichua Catholic Encyclopaedia, Quichua Indians Quechua Songs & Poems, Stories, Photos Die Quichua (auf Deutsch) Quichua (in romana) Los Quechua (en español) Books Whitten, N. E., (1976) Sacha Runa: Ethnicity and Adaptation of Ecuadorian Jungle Quichua. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. King, K. A., (2001) Language Revitalization Processes and Prospects: Quichua in the Ecuadorian Andes (Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters Press. Urton, G., (1997) The Social Life of Numbers: A Quechua Ontology of Numbers and Philosophy of Arithmetic. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. Luna, L. E., (1999) Ayahuasca Visions: The Religious Iconography of a Peruvian Shaman. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.