The Indigenous Mandinka People

Ethnonyms: Malinke, Mandika, Mandingo, Mandinko, Mandi'nka Kango Countries inhabited: Mali, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Guinea-Conakry, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Mauritania Language family: Niger-Congo Language branch: Manding

Click/tap an image to begin a high-quality, captioned slideshow and, where available, stock licensing information.

A major milestone occurs in human societies when some of its members are first dedicated to activities that do not produce food. It typically follows the transition to a sedentary (or semi-sedentary) lifestyle and marks the onset of what we recognize to be culture. In the societies of Mandé peoples such as the Mandinka, we see many examples of this.

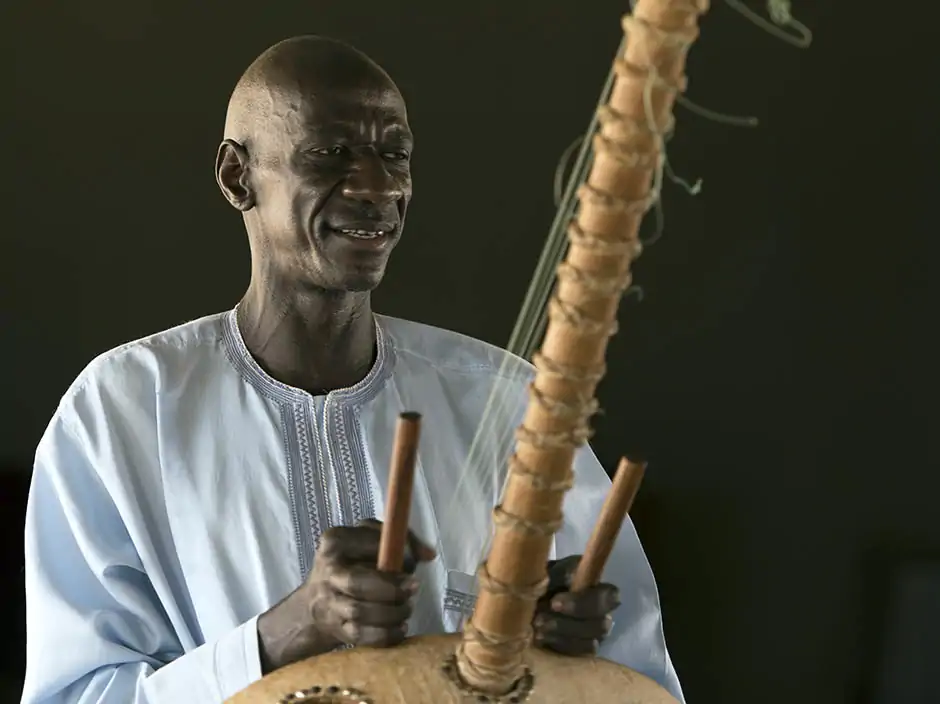

The Mandinka are a very large ethnic group indigenous to West Africa, where they have lived for many centuries. One of their cultural roles is that of storyteller/historian. Men who fulfill this role are called Griots (Jalis in the Mandinka language). They often accompany their storytelling by playing a traditional, harp-like musical instrument called the Kora. Then, the storytelling is done in song. This cultural practice, however, is not simply a form of entertainment (although it can sometimes be for that purpose). Griots are the safe-keepers of Mandinka oral history. Their storytelling is ritual and often recalls their people's history all the way back to the ancient Mali Empire. This art form is passed down in Mandinka tradition through the male lineage.

Musical performance in Mandinka society is not restricted to males. Indeed another hallmark of the onset of culture, in general, is the pervasion of ceremonial music.

Ceremonial music in West Africa is closely linked with ceremonial dance. Each ethnic group has its own variations and, for the Mandinka, women are far more likely than men to be seen participating in such ceremony. Their dance style focuses mainly on arm and leg movement. They are also more likely than men to be playing the accompanying music. Traditionally, these music and dance ceremonies have been associated with village celebrations such as crop harvest, the recognition of a new village headman or a successful fishing catch.

While the Griot tradition is an example of Mandinka indigenous knowledge, its preservation and its communication, it would seem less likely that the same can be said of traditional Mandinka dancing. Yet, Abiola (2019), has argued that this is exactly the case. She studied dance among the Mandinka extensively and found that, like the Griot tradition, it captures, preserves and communicates Mandinka indigenous knowledge.

To some degree, political decentralization is more prevalent in post-colonial West Africa than it was during colonial times. For the Mandinka, this means that political organization today, at least at the village level, can be closer to the traditional norm. That norm dictates that the original settlers of a village (or community of closely-located villages) pass down political leadership and authority through the male line — eldest son to eldest son. (The Mandinka are a patrilineal society.)

There is one exception to this norm: when a village headman (Alkalo) dies with no male children. That happened recently in the remote interior Gambian village of Jufureh. The lady pictured above, Tako Taal, is the head of Jufureh because she has no brothers. Her eldest son will become the next head of the village.

Jufureh is interesting for a different reason also. Perhaps the best-known, globally, Mandinka is Kunta Kinte. He is the main character in Alex Haley's novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family. It remains unclear how historically accurate the novel is — and whether Kunta Kinte was a real person. But what is not in doubt is the theme of the basic story: Many indigenous Africans, including Mandinkas, were captured, sold and transported during the transatlantic slave trade. Many African-Americans today are descended from Mandinkas.

The history of the Mandinka in slavery also forms a part of their traditional social stratification. (To understand this, it has to be noted that the Mandinka were also a source people in the trans-Saharan slave trade, which both pre-dated and overlapped the transatlantic slavery period.) They have a broad concept of royalty/nobility. Some clan names survive from the recognized royalty of the ancient Mali Empire. Others are non-royal descendants whose family names coincide with important historical figures (both Mandinka and others) from that time. These lineages are preserved via the Griot tradition and these people are considered to be at the top of the social ladder. The village headman is almost always a member of this group. At the bottom are the descendants of slaves and prisoners of war (those two groups were not mutually exclusive). Slavery, as we understand it historically, is now illegal everywhere. This group today includes hired hands who provide wage-labor to, for example, farmers.

The Mandinka are said to be almost 100% Muslims today. But that is a misleading statement. The spread of Islam through West Africa happened over a long period and is not reliably documented in detail. So the conversion of the Mandinka to Islam would have occurred at different times in different areas. In any case, the spread of ideas (not just religious ones) among societies is already a complex topic to study. Given the prescriptive nature of orthodoxy and doctrine in most religions, we can only understand religious conversion in context.

Another hallmark of culture is the appointment of people to dedicated religious/spiritual roles. For the Mandinka, this predates Islam. We see it, for example, in the tradition of hereditary title to village headman. The Mandinka believe that the eldest male among the original settlers of a village or area would have had unique powers to mediate with the spirits of that land. Furthermore, he would have passed down this power through the male blood line. This is part of a belief system of Animism, not Islam.

Another example has its roots in the Islamic tradition of Sufism. Sufis played a key role in the spread of Islam — particularly to and within Africa. In West Africa, as noted above, indigenous peoples already had religious (insofar as Animism can be called a religion) leaders and teachers. The two traditions morphed over time into the role of the marabout. Today, a marabout in Mandinka society may play many roles. Although he is usually versed in the Qur'an, he might write down some of its passages to be included in custom-made amulets that are then worn for protection from evil spirits or from other forms of harm or to effect the demise of enemies. Or he may control (or even create) those spirits using, for example, animal sacrifice. Or he may cure someone possessed by evil spirits using traditional, herbal medicine. In addition to these Animist practices, many Mandinka observe December 25 as a holiday.

Most Mandinkas still live in small, rural settlements today. As elsewhere in the developing world, this often restricts their access to formal education. Females in particular still suffer from a low literacy rate. Yet literacy among the Mandinka has two aspects. They use both Roman and Arabic scripts. The Roman script is used in modern schools. Here, it is the inability or the unwillingness of parents to send girls to school that accounts for their lower literacy rate. The Arabic script is used in the semi-formal Islamic schools often run by marabouts. Only boys are admitted into these schools.

Beside their continued location in small, traditional villages, most Mandinkas still rely on subsistence farming and fishing for their livelihood. It is here that their indigenous knowledge thrives. Their earliest migration was westward from the Niger River. This was followed by a southeastern movement. They successfully exploited the natural resources they encountered and formed a succession of kingdoms (including fourteen in the Senegambia region of Senegal and The Gambia). They also established new trading routes as they expanded their territory. For a while, they even successfully resisted European colonial forces.

Maize (corn), millet, rice and sorghum have traditionally been Mandinka subsistence staples, although they have recently added peanuts as a cash crop. Livestock is also, but less commonly, kept, eaten, ritually sacrificed and traded (including within their own communities as bride payment). In times past the Mandinka were among the main traders in the region, but very few are concerned exclusively with trade these days. When they are, it is mainly their craft products that form the bulk of the merchandise.

Human labor was once strictly gender- and age-specific among the Mandinka. Today, some gender roles are more blurred. So it is quite common to see women and girls tending crops as well as working alongside men and boys during harvest time. They are also more likely to be involved in art and craftwork than before. Nonetheless, other traditional gender- and age-specific roles are still observed and strictly enforced. For example, only Mandinka men will leave their village to pursue wage-labor income. Daily household tasks like meal preparation and caring for young children is still a female-only endeavor.

This societal norm is established and maintained through a series of youth affiliations. (The closest institution in our society would be a youth club.) The Islamic schools for young boys mentioned above are one example, but there are others. The Mandinka mark the passage into adulthood with ritual circumcision for boys and genital mutilation for girls. Before undergoing this, young boys and girls join separate male- or female-only affiliations (run by adults) that prepare them for the norms of adult life by teaching them what is acceptable conduct and what is taboo. After being inducted into adulthood, there are more politically-oriented affiliations they may join as well as charitable ones. It is during these early adult years that they form their views to be passed on to the next generation.

Photography copyright © 1999 -

2026,

Ray Waddington. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 1999 -

2026,

The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R. (2020), The Indigenous Mandinka People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved February 4, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Mandinka>

Web Links

Indigenous Dances of West Africa (short film on YouTube)

Tragic End For Mamadoe — The Mandinka Faith Healer

Kingdoms of West Africa — Mali

Books

Abiola, O.M., (2019) History Dances: Chronicling the History of Traditional Mandinka Dance. New York, NY: Routledge.

Charry, E.S., (2000) Mande Music: Traditional and Modem Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Mommersteeg, G., (2011) In the City of the Marabouts: Islamic Culture in West Africa. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Quinn, C.A., (1972) Mandingo Kingdoms of the Senegambia: Traditionalism, Islam and European Expansion. London: Longman Press.